New Book on Nazi-Era Humor

By David Crossland

A new book about humor under the Nazis gives some interesting insights into life in the Third Reich and breaks yet another taboo in Germany's treatment of its history. Jokes told during the era, says the author, provided the populace with a pressure release.

Hitler visits a lunatic asylum. The patients give the Hitler salute. As he passes down the line he comes across a man who isn't saluting.

"Why aren't you saluting like the others?" Hitler barks.

"Mein Führer, I'm the nurse, I'm not crazy!" comes the answer.

That joke may not be a screamer, but it was told quite openly along with many others about Hitler and his henchmen in the early years of the Third Reich, according to a new book on humor under the Nazis.

But by the end of the war, a joke could get you killed. A Berlin munitions worker, identified only as Marianne Elise K., was convicted of undermining the war effort "through spiteful remarks" and executed in 1944 for telling this one:

Hitler and Göring are standing on top of Berlin's radio tower. Hitler says he wants to do something to cheer up the people of Berlin. "Why don't you just jump?" suggests Göring.

A fellow worker overheard her telling the joke and reported her to the authorities.

The author, German film director and screenplay writer Rudolph Herzog, isn't trying to make readers laugh. He wants to examine the Nazi period from a different perspective, and sees contemporary jokes as a good way of showing people's true feelings at the time.

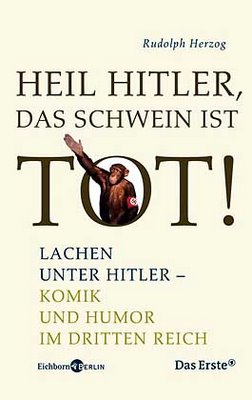

"Jokes reflect what really affects, amuses and angers people. They provide an inner view of the Third Reich that possesses an authenticity one usually misses when reviewing other literary texts," says Herzog, 33, whose book "Heil Hitler, The Pig is Dead" -- the punchline to another Hitler joke -- goes on sale in September. "Political jokes weren't a form of active resistance but valves for pent-up public anger. They were told in pubs, on the street -- to let off steam with a laugh. This suited the Nazi regime which was deeply humorless."

Releasing steam

Many Germans were angry about Nazi fat cats getting top jobs in the government and industry, but they didn't rebel. They just told jokes:

"A senior Nazi visits a factory and asks the manager whether he still has Social Democrats among his workforce.

"Yes, 80 percent," comes the reply.

"Do you also have members of the Catholic Center Party?" "Yes, 20 percent," the manager responds.

"Don't you have any National Socialists?"

"Yes we're all Nazis now!"

The vanity of the Nazi top brass was the butt of many jokes:

"Göring has attached an arrow to the row of medals on his tunic. It reads 'continued on the back.'"

Such jokes were harmless to the Nazis and didn't reflect opposition to them, says Herzog. He contrasts it with the desperate gallows humor of Germany's Jews as the noose tightened during the 1930s and in the war years:

"Two Jews are about to be shot. Suddenly the order comes to hang them instead. One says to the other "You see, they're running out of bullets."

Such jokes told by Jews were a form of mutual encouragement, an expression of the will to survive. "Even the blackest Jewish humor expresses a defiant will, as if the joke teller wanted to say: I'm laughing, so I'm still alive," says Herzog.

His book, based on contemporary literature, diaries and interviews with 20 people who lived through the Third Reich, comes to some uncomfortable conclusions: From an early stage, Germans were well aware of their government's brutality. And the country wasn't possessed by "evil spirits" nor was it hypnotised by the Nazis' brilliant propaganda, he says. Hypnotized people don't crack jokes.

Hitler didn't hypnotize Germans

"If you laugh about Hitler, you rob him of the metaphysical, demonic capabilities that the post-war apologists attributed to him," says Herzog. That makes it all the more astounding that the "hollow fairground magic of the Nazis", which was laid bare in contemporary satire and literary testimony, resulted in the Holocaust, he says. "The Germans were by no means powerless victims of propaganda. Many saw through the games played by Goebbels and his consorts. This didn't change the fact that the country was sucked down into a whirlpool of crime in the space of just a few years."

This joke about Dachau concentration camp, opened in 1933, shows people knew early on they could be imprisoned on a whim for expressing an opinion:

Two men meet. "Nice to see you're free again. How was the concentration camp?"

"Great! Breakfast in bed, a choice of coffee or chocolate, and for lunch we got soup, meat and dessert. And we played games in the afternoon before getting coffee and cakes. Then a little snooze and we watched movies after dinner."

The man was astonished: "That's great! I recently spoke to Meyer, who was also locked up there. He told me a different story."

The other man nods gravely and says: "Yes, well that's why they've picked him up again."

Breaking taboos

Herzog's book is just the latest indication of a fundamental shift in Germany's treatment of its Nazi history in recent years. As the wartime generation dies out, the children and grandchildren are taking a more detached view of the past, and a number of taboos have been broken as a result.

In 2004, the German film "Downfall" about Hitler's last days in his bunker portrayed the dictator's human side. Earlier this year, big swastika banners went up in Berlin during the filming of Germany's first comedy about Hitler -- something that would have been unheard of just a few years ago.

"Each new generation of Germans has to get to grips with the past," Herzog says. "Taboos have been broken. With the distance of time you see the ridiculous side of this regime, but without forgetting its evil. We're still too close to it for that."

German society quickly became militarized after the Nazis took power. New organisations were created, each with its own range of uniforms. One joke making the rounds was that the actual army would in future wear civilian clothes so that it could recognized.

Many found the Heil Hitler salute with its outstretched arm ridiculous. A circus director in the western city of Paderborn, a confirmed Social Democrat opponent of the Nazis, trained his chimpanzees to raise their right arm whenever they saw a uniform, and they even took to saluting the postman.

He was denounced and a received an official notice forbidding the chimpanzees from making the salute and threatening "slaughter".

Another joke that illustrated life under the Nazis was this one:

"My father is in the SA, my oldest brother in SS, my little brother in the HJ (Hitler Youth), my mother is part of the NS women's organisation, and I'm in the BDM (Nazi girls group)."

"Do you ever get to see each other," asks the girl's friend?

"Oh yes, we meet every year at the party rally in Nuremberg!"

The Nazis passed laws in 1933 and 1934 banning comments that criticized the regime. But court cases usually resulted in just a warning or a fine, and alcohol was taken as a mitigating factor. Anti-Jewish jokes, of course, were welcome -- and they flourished in the 1930s reflecting the anti-Semitism present in German society.

Pride and sarcasm

Rearmament and economic revival in the 1930s and Hitler's early victories brought a wave of national pride:

"What does it mean when the sky is black? There are so many aircraft in the air that the birds have to walk."

Many Germans credited Hitler with restoring the country's honor in the wake of its World War I defeat and the economic crisis and political turbulence of the 1920s.

During the war, the regime tried to entertain the troops and distract the civilian population by promoting comedy films and harmless caberets. Jokes about Italy's disorganized army also featured. Here's one:

The German army HQ receives news that Mussolini's Italy has joined the war.

"We'll have to put up 10 divisions to counter him!" says one general.

"No, he's on our side," says another.

"Oh, in that case we'll need 20 divisions."

As it became clear that Germany was losing the war and Allied bombing started wiping out German cities, the country turned to bitter sarcasm:

"What will you do after the war?"

"I'll finally go on a holiday and will take a trip round Greater Germany!"

"And what will you do in the afternoon?"

But telling such jokes was dangerous. "Defeatism" became an offense punishable by death and a joke could get you executed. "With the defeat at Stalingrad and the first waves of the bombing campaigns against German cities, political humor turned into gallows humor, silliness gave way to plain sarcasm," says Herzog.

Humor hasn't fully recovered in Germany. "Jewish humor is famous for its sharpness and biting character and we miss that here today along with a whole range of aspects of Jewish culture," said Herzog.

Source: Spiegel Online

1 comment:

Do you know where to get this book? Is it in German? Or in English?

Post a Comment